“Is This Behavior Normal… or Should I Be Worried?”

A guide for parents wondering if their child's behavior is cause for concern—and for professionals supporting families through these questions. What Does "Normal" Really Mean?

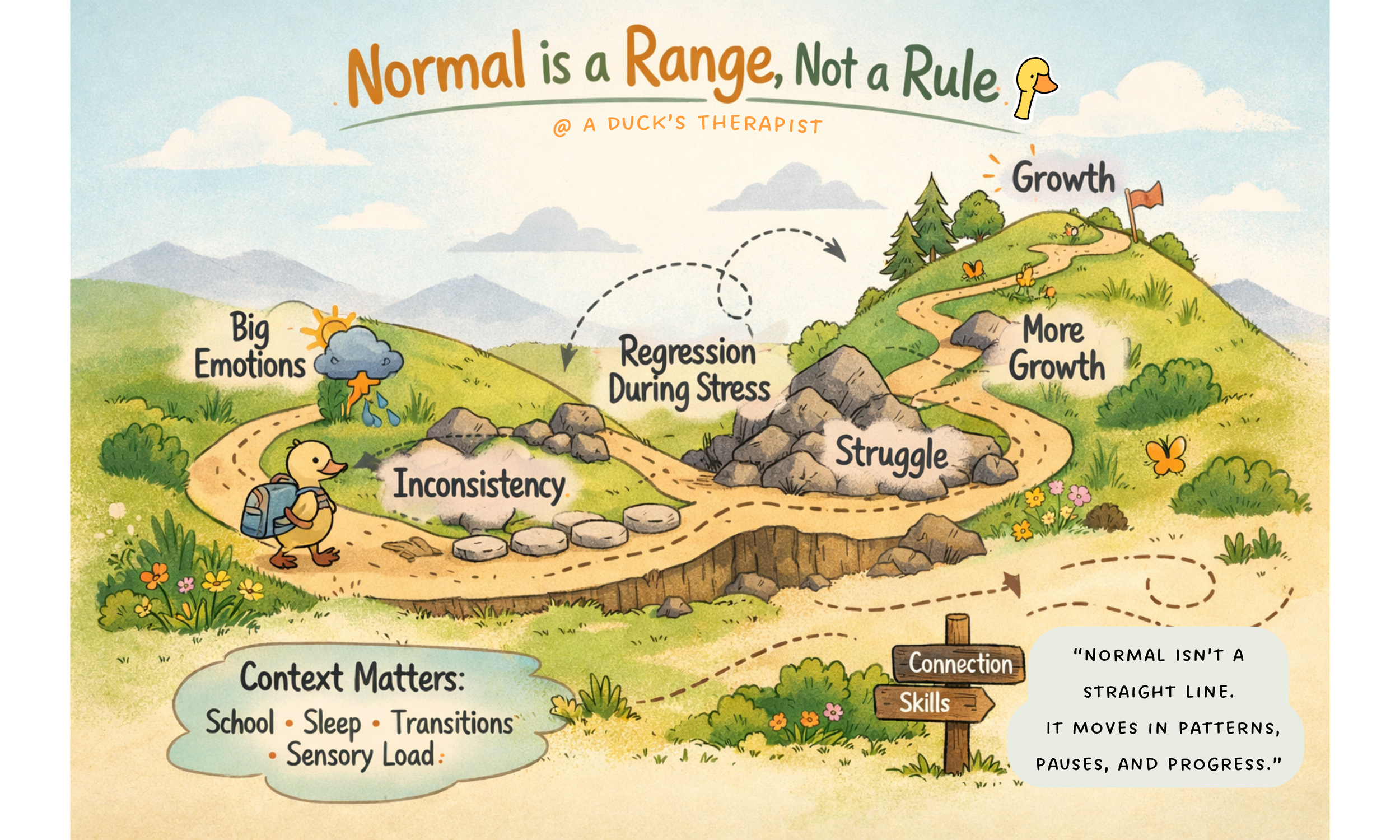

When we ask whether something is normal, we usually imagine a clear line — this side is fine, that side is concerning.

But as most parents know, kids don't fall neatly into categories. They live in the nuanced, complicated middle—where most of childhood actually happens.

Normal is a range, not a rule.

It includes:

Big emotions

Inconsistency

Regression during stress

Periods of struggle followed by growth

Some kids feel things deeply. Some kids react loudly. Some kids hold it together all day and fall apart at home. None of that automatically means something is "wrong."

At the same time, normal doesn’t mean easy, and common doesn’t mean harmless.

That’s where nuance matters.

"Development isn't a straight line from Point A to Point B. It's more like a winding path through varied terrain—and every child's journey includes rocky patches, detours, and growth spurts."

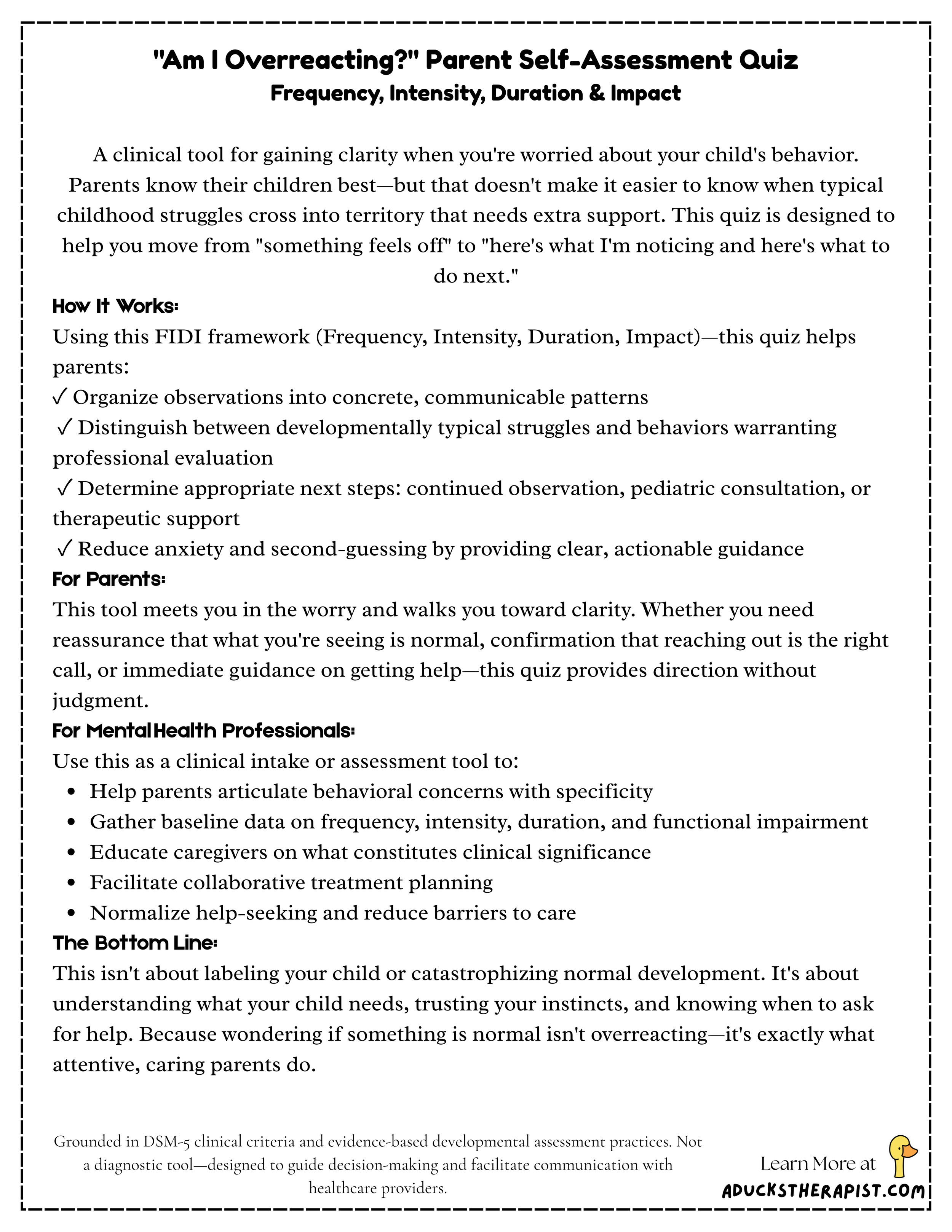

A Helpful Framework: FIDI

Frequency, Intensity, Duration, and Impact

Instead of asking "Is this normal?", try asking:

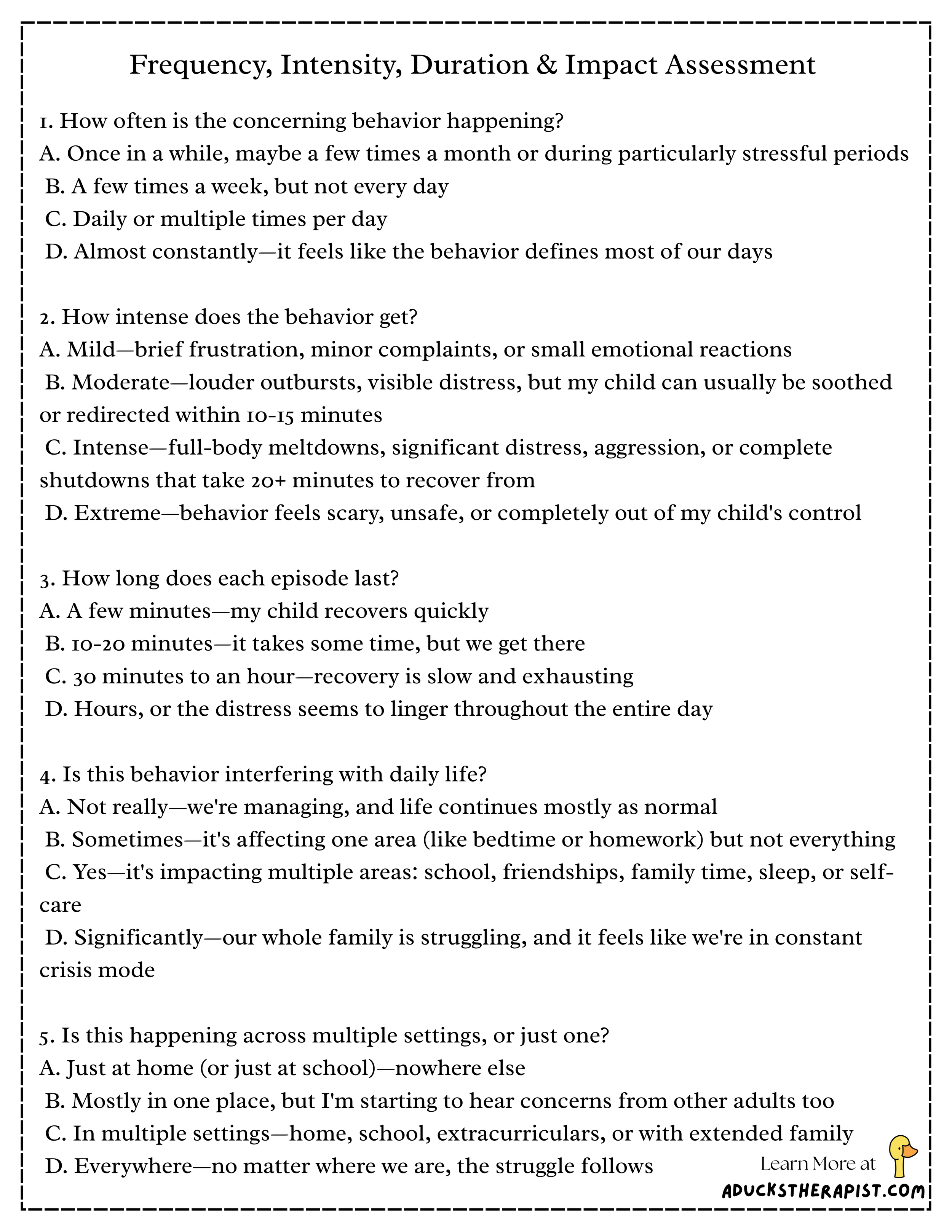

1. Frequency

How often is this happening?

Occasionally?

Daily?

Multiple times a day?

2. Intensity

How big does it get?

Mild frustration?

Full-body meltdowns?

Fear or distress that feels hard to soothe?

3. Duration

How long does it last?

Minutes?

Hours?

Days at a time?

4. Impact

Is it interfering with daily life?

School performance or attendance

Sleep quality or routine

Relationships with family or peers

Family functioning overall

Your child's sense of self or well-being

One difficult moment usually isn't the concern. Patterns provide much more information.

The frequency-intensity-duration-impact (FIDI) framework is derived from standard clinical assessment criteria used in mental health diagnosis and treatment planning, including the DSM-5-TR diagnostic criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2022) and evidence-based assessment practices in developmental psychopathology (Cicchetti & Toth, 2009; Wakschlag et al., 2012).

“Wondering whether something is “normal” doesn’t mean you’re anxious, dramatic, or failing as a parent.

It means you’re paying attention. And paying attention is one of the most important protective factors kids have.”

Behavior Is Communication, Not a Diagnosis

This is one of the most important things to understand about kids and mental health.

Children don't show stress the way adults do.

They show it through:

Meltdowns

Anger

Withdrawal

Clinginess

Avoidance

Physical complaints like stomachaches or headaches

These behaviors aren't character flaws. They're signals.

A child who melts down isn't being manipulative. A child who shuts down isn't being lazy. A child who lashes out isn't choosing chaos.

Behavior is information. It tells us a child is overwhelmed, under-resourced, or struggling with demands that exceed their current coping skills.

This perspective shifts everything. Instead of asking "What's wrong with my child?" we can ask "What is my child trying to tell me?" or "What does my child need right now that they don't have?"

Look for Patterns, Not Just Hard Days

Parents often come in worried about their child's worst moments—and that makes sense. Those moments are exhausting and scary.

But what helps most is zooming out.

Ask yourself:

Does this happen everywhere, or mostly in one setting (home, school, grandma's house)?

Are there specific triggers (transitions, academic demands, sensory overload, separation)?

What seems to help, even a little?

Has this changed over time, or stayed consistent?

When does your child seem most regulated and capable?

Patterns help clarify whether something is part of typical development, a response to environmental stress, or a sign that more support may be needed.

The Environment Matters

Sometimes the issue is the fit between the child and their environment.

Things that can amplify emotional and behavioral struggles include:

Increased academic demands or developmental transitions

Sensory-heavy or overstimulating classrooms

Sleep deprivation or irregular sleep schedules

Hunger or inconsistent daily routines

Big life changes (new sibling, move, divorce, loss, family illness)

Social stress, peer conflict, or bullying

Lack of downtime, play, or physical movement

When kids don't yet have the skills to manage these demands, their nervous systems do the talking.

That doesn't mean they're broken. It means they need support.

Often, environmental modifications—more sleep, sensory breaks, clearer routines, reduced demands—can make a significant difference before we even consider whether there's an underlying clinical concern.

Important: Is This Assessment Right for You?

This tool is designed for parents experiencing persistent concern about their child's behavioral or emotional patterns.

Appropriate use:

You have specific, ongoing worries about your child's behavior

You're trying to determine if professional consultation is warranted

You need a framework to organize observations before speaking with providers

Not appropriate for:

General curiosity without specific concerns

Routine "check-ins" on child development

Parents not currently experiencing worry or uncertainty

Clinical note: Unnecessary assessment can increase parental anxiety and hypervigilance. If you are not currently concerned about your child's functioning, this tool is not indicated. Normal childhood development includes struggle, inconsistency, and hard days—none of which require assessment in the absence of parental concern or functional impairment.

If you're unsure whether this applies to you, ask yourself: "Have I been repeatedly worrying about this, or am I just curious?" If it's the latter, you don't need this quiz.

When "Normal" Becomes "Needs Support"

This is the part pretty much all parents are worried about—so let's be clear and gentle.

Needing support does not mean something is "wrong" with your child.

It may be time to seek extra help when:

Your child seems distressed, anxious, or dysregulated more often than not

Their struggles are interfering with daily life in multiple settings

Coping skills aren't catching up with age-appropriate expectations

You feel stuck, exhausted, or unsure how to help anymore

You keep asking yourself this question

That last one matters. If you're asking yourself repeatedly whether something is normal, that itself is information worth bringing to a professional—not because you're overreacting, but because persistent worry means something needs attention, even if it's just parent support and guidance.

When to Seek Immediate Help

Some situations warrant urgent consultation with a mental health professional:

Talk of self-harm or suicidal thoughts

Aggression toward others or animals that feels out of control

Severe regression in previously mastered skills

Complete refusal to attend school for extended periods

Significant changes in eating, sleeping, or self-care

If you're seeing any of these, reach out to your pediatrician, school counselor, or mental health professional. These aren't signs of failure—they're signs your child needs more support than you can provide alone. We are SUPPOSED to help each other. Raising kids takes a village, remember?

Getting Help Is a Stepladder, Not a Cliff

Many parents hesitate to reach out because of fear of what it may mean. This is super understandable!

But help doesn't automatically mean:

Labels

Medication

Years of therapy

Something being "permanently wrong"

Judgement from others ( All parents will encounter problems with their kids; you are not alone)

Support could be:

Parent coaching to understand your child's nervous system

Skill-building around emotional regulation or executive function

Short-term therapy (6-12 sessions) focused on specific challenges

School accommodations or 504/IEP supports

Better understanding of neurodevelopmental differences

Family therapy to improve communication patterns

Early support is preventative, not extreme.

Getting help when things are hard—but not yet in crisis—gives kids the best chance to build skills, confidence, and resilience. It's not admitting defeat. It's being proactive.

Trust Your Instincts—(Without panicking)

You know your child better than anyone else.

If something feels off, it's worth paying attention to—without jumping to any extremes.

Using tools like pattern-tracking and the frequency–intensity–duration–impact lens helps balance intuition with clarity. It gives you language, not fear. It helps you communicate with pediatricians, teachers, and therapists in ways that get your child the support they need.

Your instincts matter. And pairing those instincts with observation creates powerful advocacy.

Citations:

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2019). Mental health screening and assessment tools for primary care. Pediatrics, 144(6), e20192894.

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.).

Cicchetti, D., & Toth, S. L. (2009). The past achievements and future promises of developmental psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(1-2), 16-25.

Wakschlag, L. S., Choi, S. W., Carter, A. S., Hullsiek, H., Burns, J., McCarthy, K., Leibenluft, E., & Briggs-Gowan, M. J. (2012). Defining the "disruptive" in preschool behavior: What diagnostic observation can teach us. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 15(3), 183-201.

Winters, N. C., Collett, B. R., & Myers, K. M. (2005). Ten-year review of rating scales, VII: Scales assessing functional impairment. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 44(4), 309-338.