Jumping to Conclusions: Fortune Telling and Mind Reading

This blog uses evidence-based research from CBT (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy)

We all think we have a solid grasp of reality. We navigate complex relationships, demanding careers, and endless daily decisions with a sense of confidence. But there’s a sneaky cognitive distortion that can trip us up without warning: jumping to conclusions. This mental habit—making snap judgments or assumptions without solid evidence—can wreak havoc on our emotional well-being, relationships, and decision-making. However, this cognitive distortion is often a reflection of our own insecurities rather than being rooted in reality.

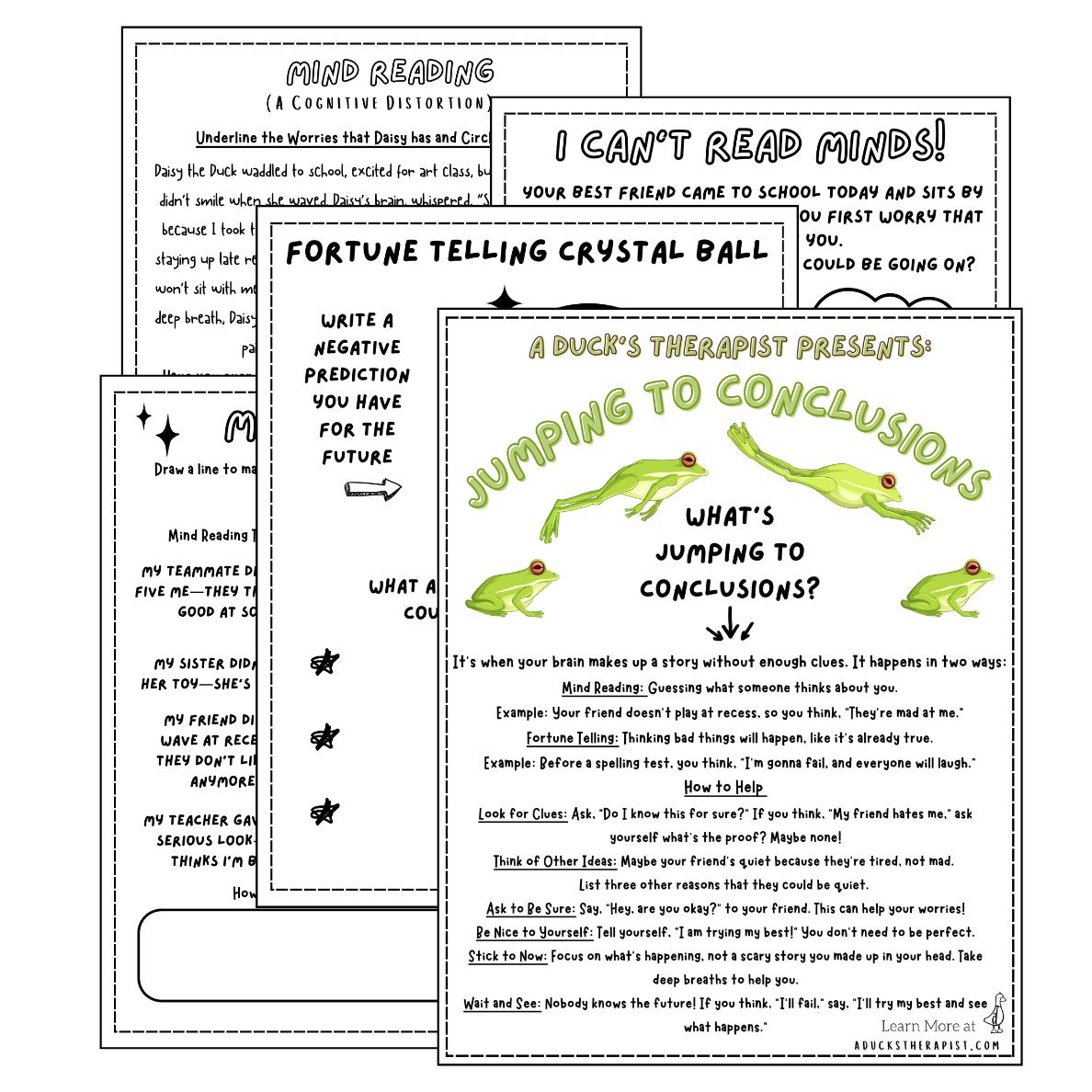

What Is Jumping to Conclusions?

Jumping to conclusions is a cognitive distortion where we make judgments or predictions without enough evidence to support them. It comes in two main flavors:

Mind Reading: Assuming we know what someone else is thinking or feeling about us.

Example: Your friend doesn’t text back promptly, and you immediately think, “They’re mad at me” or “They are annoyed at me.”

Fortune Telling: Predicting negative outcomes about the future as if they’re inevitable and already decided.

Example: Before a work presentation, you convince yourself, “I’m going to mess this up, and everyone will think I’m incompetent.”

Both forms involve creating narratives—stories we tell ourselves about situations or people—that feel real but are often rooted in speculation rather than fact.

The Damage of Creating False Narratives

When we jump to conclusions, we don’t just misinterpret a single moment; we build entire narratives that can spiral out of control. These stories we tell ourselves have real consequences:

Emotional Toll: Assuming someone dislikes you or that you’re doomed to fail can trigger anxiety, shame, or anger. These emotions drain mental energy and can lead to chronic stress or low self-esteem.

Strained Relationships: Mind-reading often leads to misunderstandings. If you assume your partner is upset with you and react defensively, you might create conflict where none existed. Over time, this erodes trust and connection.

Missed Opportunities: Fortune telling can stop you from taking risks. If you convince yourself a job interview will go poorly and the employer will believe you’re not qualified, you might not prepare adequately or even show up. You sabotage yourself, making your biggest fears come true.

Self-Fulfilling Prophecies: The narratives we create can shape our actions. If you believe a friend is pulling away, you might withdraw first, inadvertently pushing them away and “proving” your assumption correct.

These narratives are particularly harmful because they feel so convincing. Our brains treat them as truth, even when they’re built on flimsy evidence—or none at all.

Why and How We Do This…

Jumping to conclusions feels like a mental shortcut, but gone wrong. Our brains are wired to make quick judgments to save time and energy, a trait that helped our ancestors survive in dangerous environments. But in modern life, this tendency can misfire. Here’s how it plays out:

We Fill in the Gaps: When faced with ambiguity—like a vague email from a boss or a partner’s neutral facial expression—we instinctively fill in the blanks. Instead of seeking clarification, we assume the worst.

We Project Our Fears: The conclusions we jump to often mirror our deepest insecurities. If you’re worried about being unlikable, you might interpret a coworker’s silence as disdain. If you fear failure, you might predict disaster before even trying.

We Seek Patterns: Our brains love patterns, even when they’re false. A single rejection might lead you to conclude, “Nobody ever wants to work with me,” even if the evidence suggests otherwise.

For adults, this distortion can appear in high-stakes contexts, such as relationships, workplaces, or social settings, where the stakes feel personal and the pressure to “get it right” is intense.

Rooted in Insecurity, Not Reality

The conclusions we jump to are rarely about the other person or the situation. They’re about us—our fears, insecurities, and worst-case scenarios. When we mind read, we’re not actually reading someone else’s thoughts; we’re projecting our own worries onto them. That coworker who didn’t smile? You might assume they’re judging you because deep down, you’re afraid of being seen as incompetent. That unanswered text? It might spark thoughts of rejection because you’re grappling with feelings of unworthiness.

This distortion thrives in the soil of insecurity. If you’re confident in your worth, you’re less likely to assume others are thinking poorly of you. But when self-doubt creeps in, every ambiguous moment becomes a canvas for your fears to paint a grim picture. The thoughts we attribute to others—“They think I’m a failure,” “They don’t respect me”—are often the very criticisms we secretly level at ourselves.

The Mirror of Mind Reading

Mind reading, in particular, is like holding up a mirror to our own psyche. The assumptions we make about others’ thoughts are often our own inner dialogues in disguise. If you’re worried about being “not good enough,” you might assume your boss is disappointed in your work. If you fear abandonment, you might interpret a friend’s busyness as disinterest. These are our worries, not their realities.

This projection can trap us in a cycle of self-criticism. By assuming others are thinking the worst, we reinforce our own negative beliefs about ourselves. Over time, this can erode confidence and make us feel isolated, as we convince ourselves the world is judging us as harshly as we judge ourselves.

Breaking Free from the Trap

Pause and Check the Evidence: When you catch yourself assuming someone’s thoughts or predicting a negative outcome, ask, “What evidence do I have for this?” Often, you’ll find the answer is “none” or “not much.”

Consider Alternatives: Instead of latching onto the worst-case scenario, brainstorm other explanations. Maybe your friend didn’t reply because they’re busy, not because they’re mad. Maybe your presentation will go fine if you prepare.

Test Your Assumptions: If you’re mind reading, check in with the person. A simple, “Hey, I noticed you seemed quiet—everything okay?” can clarify things and save you from spiraling.

Practice Self-Compassion: Since jumping to conclusions often stems from insecurity, work on building self-worth. Remind yourself that you don’t need to be perfect to be valued, and others’ opinions don’t define you.

Seek Reality Over Narrative: Focus on what’s actually happening, not the story you’re telling yourself. Ground yourself in the present moment through mindfulness or journaling to separate fact from fiction. Tell yourself that you cannot possibly know what's going to happen, and you'll just have to wait and see. Nobody knows all the answers or can predict the future.

How Kids Experience Jumping to Conclusions

Children, like adults, can fall into the cognitive distortion of jumping to conclusions, but the way it manifests in kids is shaped by their developmental stage, emotional maturity, and limited life experience. This distortion—making snap judgments without evidence, either through mind reading (assuming they know what others think) or fortune telling (predicting negative outcomes)—often shows up in ways that reflect their egocentric worldview and heightened sensitivity to social dynamics.

Fortune Telling in Kids

How it looks: Kids may predict negative outcomes with certainty, especially in unfamiliar or challenging situations. For example, “I’m going to fail this math test,” “Nobody will want to be my partner,” or “I’ll mess up my lines in the school play.”

Why it happens: Kids have less experience coping with uncertainty, so their brains default to worst-case scenarios to prepare for potential threats. Anxiety about failure or rejection, common in childhood, fuels these predictions. They also lack the cognitive flexibility to realistically weigh probabilities.

Mind Reading in Kids

How it looks: Kids often assume they know what others—peers, teachers, or parents—are thinking about them, usually in negative terms. For example, a child might think, “My friend didn’t play with me at recess; they hate me,” or “My teacher gave me a stern look, so she thinks I’m bad.”

Why it happens: Children are naturally self-focused and may interpret others’ actions as being about them. Their still-developing ability to perspective-take means they struggle to consider alternative explanations (e.g., “My friend might be upset about something else”). Insecurity about fitting in or being liked can amplify these assumptions.

Developmental Context

Younger children (ages 4–8) may jump to conclusions due to magical thinking or limited logic. For example, a preschooler might think, “Mom’s mad because I didn’t eat my carrots,” assuming their actions control others’ emotions.

Older children and preteens (ages 9–12) are more socially aware, making them prone to mind-reading in peer groups. They might obsess over perceived slights, like, “Everyone’s laughing because of me.”

Teens, with their heightened self-consciousness, may amplify both mind-reading and fortune-telling, especially about social status or academic performance, due to intense pressure to belong and succeed.

Why It’s Detrimental for Kids

Like adults, kids’ conclusions often stem from insecurity or fear. A child worried about being “dumb” might assume a teacher’s correction means, “She thinks I’m stupid.” These assumptions reflect their own self-doubts, not reality. Kids are especially vulnerable because their self-concept is still forming, and they rely heavily on external validation from peers and adults.

Emotional Distress: Assuming others think poorly of them or predicting failure can lead to anxiety, sadness, or low self-esteem.

Social Challenges: Misreading peers’ intentions can cause conflicts or withdrawal, making it harder to build friendships.

Academic Impact: Fortune-telling about tests or projects can discourage effort, creating a cycle where the fear of failure leads to underperformance.

Reinforcing Negative Beliefs: Over time, these distorted thoughts can solidify into core beliefs, like “I’m not likable” or “I’m always going to mess up,” shaping their self-image into adulthood.

How To Help

Reframe Fortune Telling with Possibilities

What to do: When kids predict failure, help them see multiple outcomes. For example, if they say, “I’ll mess up at my soccer game,” respond, “That’s one possibility, but what else could happen? Maybe you’ll score, or maybe you’ll have a lot of fun.” Help kids see that there are always multiple ways that a situation can go!

Why it helps: This shifts their focus from doom-and-gloom to a growth mindset, emphasizing effort and resilience.

Build Self-Esteem to Reduce Insecurity

What to do: Praise effort over outcomes and celebrate their unique strengths. For example, “I love how hard you worked on that project!” or “You’re such a kind friend.” Create opportunities for small successes, like mastering a new skill.

Why it helps: A strong sense of self-worth makes kids less likely to project insecurities onto others’ actions or assume the worst.

For teens: Encourage self-reflection, such as journaling about what they’re proud of, to counteract self-critical thoughts.

Normalize Mistakes and Uncertainty

What to do: Teach kids that it’s okay not to know what others think or how things will turn out. Share stories of your own mistakes or times you misread a situation, emphasizing how you learned from it.

Why it helps: Normalizing uncertainty reduces the pressure to “figure everything out,” making kids more comfortable with ambiguity.

Example: “I once thought my friend was mad at me, but it turned out she was just stressed. It’s okay to guess wrong sometimes!”

Use Stories and Media

What to do: Read books or watch shows with kids that highlight misunderstandings, then discuss them.

Why it helps: Stories make abstract concepts concrete and relatable, helping kids see the consequences of jumping to conclusions.

Model Healthy Thinking

What to do: Show kids how you handle ambiguity without assuming the worst. For example, if someone cuts you off in traffic, say, “Maybe they’re in a rush or didn’t see me,” instead of “They’re such a jerk!”

Why it helps: Kids learn by observing. Modeling balanced thinking teaches them to consider multiple perspectives.

Validate Feelings, Then Question Assumptions

What to do: Acknowledge their emotions before challenging their thoughts. Ask open-ended questions to explore their conclusions. For example, if a child says, “My friend hates me,” respond with, “That sounds really upsetting. What makes you think they feel that way? Could there be another reason they didn’t sit with you?”

Why it helps: Validation makes kids feel heard, opening the door to rational discussion. Questions encourage critical thinking without dismissing their concerns.

For younger kids: Use simple language, like, “That feels yucky, huh? Maybe your friend was just tired from soccer yesterday. How about you ask them tomorrow?”

Teach the Evidence Game

What to do: Help kids evaluate their assumptions by asking, “What’s the proof for this thought? What’s the proof against it?” For example, if they say, “I’m going to fail my spelling test,” ask, “What makes you think that? Have you studied? Have you done okay on tests before?”

Why it helps: This builds cognitive flexibility, teaching kids to weigh evidence rather than trust their gut assumptions. It’s a foundational skill in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

For younger kids: Make it fun, like a detective game: “Let’s find clues! What clues say you’ll do great on this test?”

Encourage Perspective-Taking

What to do: Prompt kids to consider others’ perspectives. For example, if they think a friend is mad, ask, “What else might they be feeling? Could they be having a tough day?” Role-playing can help younger kids practice this.

Why it helps: Perspective-taking counters egocentrism and reduces mind-reading by showing that others’ actions aren’t always about them.

All content on A Duck’s Therapist is created and tested by a Licensed Professional Counselor.

Citations

Beck, A. T., & Clark, D. A. (1997). An information processing model of anxiety: Automatic and strategic processes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35(1), 49–58.

Hofmann, S. G., Asnaani, A., Vonk, I. J., Sawyer, A. T., & Fang, A. (2012). The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 36(5), 427–440

Burns, D. D. (1980). Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy. New York: William Morrow.

Alloy, L. B., & Abramson, L. Y. (2007). Judgment of contingency in depressed and nondepressed students: Sadder but wiser? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 108(4), 441–485.

Swenson, R. (2021). Mindreading, fortune-telling, and other common thinking mistakes teens make. Birchwood Psychological Services

Mental Health Center Kids. (2022). Jumping to conclusions: Why it happens and how to stop it.

Beck, J. S., & Beck, A. T. (2011). Cognitive Therapy: Basics and Beyond. Guilford Press.

Ugueto, A. M., Santucci, L. C., Krumholz, L. S., & Weisz, J. R. (2014). Problem-solving skills training. In Evidence-Based CBT for Anxiety and Depression in Children and Adolescents: A Competencies-Based Approach.